Music is a global phenomenon that can be found in every culture around the world. Music holds great importance to many cultures not only as a staple in tradition, to some it holds such importance as medicine. Indeed, the ancient Greeks believed music penetrates the body, the mind and served as medicine for the soul (Gfeller, 2002 as cited in; Thaut & Wheeler, 2010). These beliefs can also be found in religious leaders and philosophers that believed music was an important element of worship. For example, St.Basil of Caesarea believed music had the power to affect emotions and would bring worshipers to a higher state of being (Gfeller, 2002). Later in Constantinople, historical records indicate psychiatric illness were treated with music in hospitals (Dobrzynska et al., 2006). In modern times, people have returned to the belief that music hold cathartic or healing properties and can be used to cope with or be a source of therapy for mental health disorders (Yehuda, 2011).

[read more]

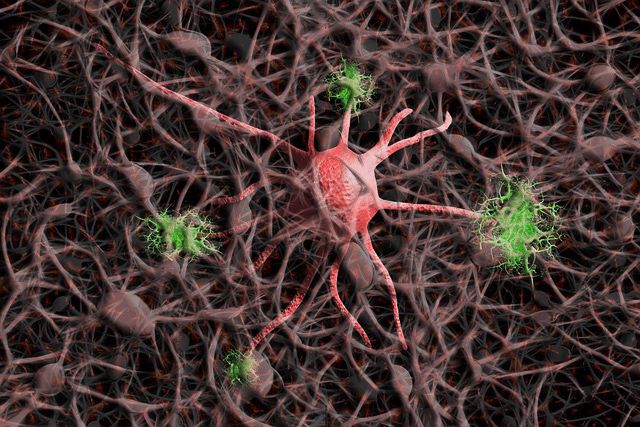

Music listening has been used as therapy agents in multiple cultures across the globe. Despite this, music as medicine research is still within its infancy and, multiple unanswered questions exist in the literature. Queries such as: ‘Can music assist our bodies to recover from ailments?’ or, ‘Does simply listening to music affect both body and mind?’ have been of interest since early music therapists (Yehuda, 2011). To answer these questions would require research and evidence from multiple fields of study spanning from Psychology to Neurophysiology. Recent experimental evidence demonstrates music listening is associated health benefits such as; reduction of in the moment stress hormones (Fancourt, Ockleford & Belai, 2014), lowered blood pressure (de Witte et al., 2020), Reduced post-operative pain (Economidou et al., 2012), enhanced recovery after stoke (Särkämö & Soto, 2012; Särkämö et al., 2013) and promote neural plasticity in multiple brain regions (Zatorre et al., 2007; Särkämö et al., 2013; Alluri et al., 2012). Despite these strides in multiple interdisciplinary fields, it appears more questions are being created, rather than questions answered.

A consistent problem asked directly in the literature is ‘Does music support neural wellbeing?’. An enquiry this broad requires defining the meaning of ‘Neural Wellbeing’ and the evaluation of the existing crisis of mental health in a fast-paced modern society. Moreover, what cannot be ignored is the lack of mental health coping techniques available to the public. This daunting request admittedly could be asking too much of music’s demonstrated capabilities. However, as researchers it is our defining role to help society achieve a better quality of life. As such, the need to test the abilities of music becomes an opportunity for better neural health and research.

The rather philosophical question ‘what is mental wellbeing’ has been postulated as: The state of well-being in which the individual realises their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community (WHO, 2017). Although this is an argument for what mental wellbeing is, it defines a subjective and objective measurable feeling, stress. What is unfortunately left unmentioned with the push for modern mental health awareness, is neural and physiological health. This rather new concept is not best described with a definition. But we rather may characterise it as a set of neural processes that contribute to healthy decision making, neural homeostasis, and bodily sensation recognition.

The feeling of psychological stress occurs when an individual perceives the environmental demands tax or exceed their adaptive capacity (Cohen, Kessler & Gordon, 1995). These insist the use of both mental and physical capabilities to successfully maneuverer the situation. Naturally, the average daily life is full of events that challenge the adaptive capacity of a single person. As stress can affect both the mind and body, chronic exposure or major acute exposure threatens our mental and neural health. As such, the mitigation, coping and alleviating of these stressors by self-volition is important for well-being.

References

Alluri, V., Toiviainen, P., Jääskeläinen, I. P., Glerean, E., Sams, M., & Brattico, E. (2012). Large-scale brain networks emerge from dynamic processing of musical timbre, key and rhythm. Neuroimage, 59(4), 3677-3689.

Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists, 3-26.

de Witte, M., Spruit, A., van Hooren, S., Moonen, X., & Stams, G. J. (2020). Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: a systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health psychology review, 14(2), 294-324.

Dobrzynska, E., Cesarz, H., Rymaszewska, J., & Kiejna, A. (2006). Music therapy–History, definitions and application. Arch Psychiatr Psychother, 8(1), 47-52.

Economidou, E., Klimi, A., Vivilaki, V. G., & Lykeridou, K. (2012). Does music reduce postoperative pain? A review. Health Science Journal, 6(3), 365.

Fancourt, D., Ockelford, A., & Belai, A. (2014). The psychoneuroimmunological effects of music: A systematic review and a new model. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 36, 15-26.

Gfeller, K. E. (2002). Music as communication.

Särkämö, T., & Soto, D. (2012). Music listening after stroke: beneficial effects and potential neural mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1252(1), 266-281.

Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M., & Huotilainen, M. (2013). Music perception and cognition: development, neural basis, and rehabilitative use of music. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(4), 441-451.

Thaut, M. H., & Wheeler, B. L. (2010). Music therapy.

World Health Organization. (2017). Mental health: strengthening our response Retrieved from

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Yehuda, N. (2011). Music and stress. Journal of Adult Development, 18(2), 85-94.

Zatorre, R. J., Chen, J. L., & Penhune, V. B. (2007). When the brain plays music: auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nature reviews neuroscience, 8(7), 547-558. [/read]

Leave a Reply